‘I Made it my Obligation to Help People get Educated About End-of-Life Care’

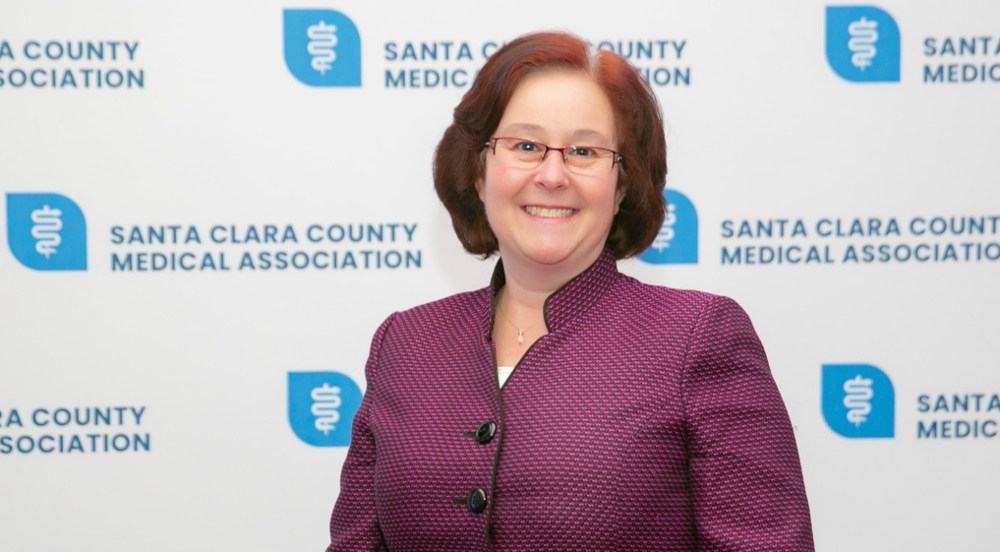

Dr. Faith Protsman is a regional medical director for VITAS Healthcare.

Faith Protsman, MD, considers the first 25 years of her medical career as the ideal foundation for her current passion and advocacy for compassionate hospice care.

“I find hospice the most rewarding care that I’ve ever provided,” says Dr. Protsman, regional medical director for VITAS Healthcare in California since early 2019.

After graduating from medical school in 1990, Dr. Protsman worked as a primary care physician and assumed numerous roles in medical leadership, medical ethics and medical education for California-area hospitals, nursing homes, palliative care programs, rehabilitation facilities, emergency departments, a hospice program and regional healthcare organizations.

“All of these experiences have given me such insight into the continuity of care and the life process that all patients go through,” she explains. “What I’ve discovered is that every little thing you do as a hospice physician makes such an impact on patients and their families. It might be kind words to someone who’s anxious or a hand on the shoulder…just knowing someone cares makes a huge difference to patients and families going through this process.”

Faith Protsman, MD, with Seema Sidhu, receives the Contribution to the Community Award from the Santa Clara County Medical Association.

Personal end-of-life issues emerged early

Dr. Protsman’s first encounter with end-of-life care, in fact, occurred while she was in medical school at the University of Miami in Florida.

“I lost my mother in a car accident, and that’s the first time I thought about how death affects all of us,” she says. Several years later, she received a 3 a.m. call informing her that her sister was in the hospital, seriously ill.

“This was just a few years after the Patient Self-Determination Act had passed in 1994. My sister was obviously very ill and not doing very well, but no one had talked to her about her choices,” she recalls. “When I got to the hospital, I told her, ‘I hope you will be angry with me for having this conversation, but just in case something happens, I want to know what you want. Do you want to be on a ventilator and intubated? Do you want CPR?’ She was coming in and out of lucidity, but she was very clear that her answer was, ‘no.’ ”

When the hospital team made efforts to intervene, Dr. Protsman vividly remembers standing between an emergency medicine physician and her sister, refusing to allow him to revive her.

“When I think back on it now, the doctor wasn’t sure whether to call security or take my word on the conversation I’d had with my sister. But he finally accepted the fact that she didn’t want extreme measures taken, and she died peacefully, with her husband on one side holding her hand, and I was on the other side holding her hand. As she passed, she had a tear in her eye, and it was just as gentle as it could be.”

As she worked through the grief of her sister’s death, Dr. Protsman gradually shifted away from intensive and emergency medicine and toward primary care and medical ethics — yet her patients continued to tell similar stories of their end-of-life wishes not being explained, discussed, documented or honored by their healthcare providers.

‘Patients have a choice’

“I made it my obligation to help people get educated about end-of-life care,” she says of her eventual shift to hospice and palliative care. “ As physicians, we’re often so focused on cures and corrections that we forget there’s a natural life process. Unfortunately, as patients get to the end of that process, they’re often forgotten. The biggest thing for me is that patients have a choice.”

“By practicing advance care planning, you are giving a gift to your family, your loved ones and your patients.”

She is a strong proponent of advance care planning (ACP), which involves honest discussions with patients to explore and document their preferences for the treatments they want and do not want at the end of life. The goal of ACP, she says, is to prevent suffering by documenting patients’ wishes as living wills or other legally accepted paperwork.

ACP’s power, she says, comes at the grassroots level, when physicians, nurses, spiritual leaders, community leaders, businesses and others embrace and promote the value of conversations about end-of-life care. In 2019, in fact, she received the Contribution to the Community award from colleagues of the Santa Clara County Medical Society for spearheading a community wide initiative to promote advance care planning and advance directives.

“I really think that patients need to have that human-to-human conversation,” she says. “By practicing advance care planning, you are giving a gift to your family, your loved ones and your patients.”

View immediate opportunities for physicians near you.

Choose a Career with VITAS

We offer a variety of full-time, part-time and per-diem employment opportunities. Employees earn competitive salaries and have the flexibility to choose a benefits package suitable to their own needs and lifestyle.

See Current Opportunities