A Day in the Life of a Male Hospice Nurse

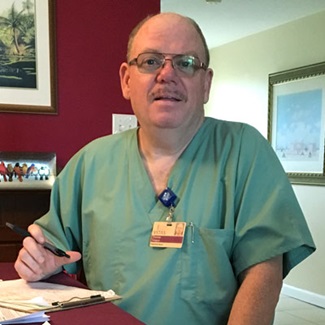

Meet Tom, a VITAS Hospice Nurse

When Tom Teague decided to give nursing a try in the early 1980s, he didn’t think twice about being a man in a female-dominated profession.

Most of the members of his family were nurses or worked in the healthcare field. So were neighbors and friends in his small Long Island hometown, where the largest employer was a state-run hospital. It didn’t matter that Tom was one of only three men among more than 50 in both his licensed practical and registered nurse classes.

Today, he’s part of a national trend: men who have chosen nursing careers to take advantage of opportunities for flexibility, autonomy, career advancement and a sense of service to others. A recent New York Times article notes that 13% of nurses are now men, up from 2% in 1960.

Hospice: A Deliberate Career Choice

While statistics indicate that male nurses tend to gravitate to technical specialties such as the emergency room, radiology and intensive care, Tom says hospice nursing puts him right where he wants to be: in patients’ homes and at their bedsides, engaging one-on-one with terminally ill patients, their families and caregivers to ensure that they enjoy the highest quality of life at the end of life.

“Hospice is something you have to decide you want to do,” says the 59-year-old, who has worked for VITAS Healthcare on a hospice team in Broward County, Florida, since 2007. Before he found his calling in hospice, he says, “I did rotations through the operating room, labor-and-delivery and the neonatal intensive care unit. I knew that kind of nursing wasn’t for me.

“Hospice is a really different way to work as a nurse, and it has been a much better niche for me. I like being independent, and I’m in my own car,” he says. “We’re all part of a VITAS team, but I’m dealing one-on-one with my patients. Most of the time, I’m very much on my own.”

Tom is aware of the misconceptions and preconceived notions about male nurses. But like several other male VITAS nurses, he has not experienced prejudices or negative encounters because of his gender.

“Occasionally, elderly patients can be confused and they’ll assume I’m a doctor,” he explains. “I tell them I’m the nurse, not the doctor … and they’ll call me ‘Dr. Tom’ anyway.

“But in my 10 years of nursing with VITAS, only twice have I run into situations where gender has been an issue. Both times it was a family member who said something along the lines of, ‘You’re so nice and helpful, but my father doesn’t want a male nurse,’ or ‘We really like you, but our mom prefers a female nurse.’ And as a team, we honor their preferences.”

A Typical Day: Needed Care, Unexpected Challenges

Prior to VITAS, Tom worked in psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, community hospitals and a veterans nursing facility. Hospice, as he notes, is different.

Each day, he climbs into his Chevy Impala to visit five to six patients in their homes. He acts primarily as a case manager who updates and reviews patient records and asks questions: Are you eating? Are you drinking? Are you in any pain? Do you have any new symptoms? He monitors vital signs, looks for changes that indicate decline, orders equipment, renews prescriptions via his company-issued iPhone, and coordinates care with his team members.

In a calm but reassuring voice, he also speaks compassionately and frankly with family members about what he’s seeing and what’s ahead. He consults with fellow nurses and calls the team doctor when the care plan needs to be revised. He consults the chaplain or social worker when patients and families need psychosocial or spiritual support.

And he fills out forms, whenever and wherever he can—at patients’ dining room tables, at the bedside, in the front seat of his idling car. Its trunk holds a cornucopia of patient supplies: bandages and wound dressings, adult diapers, bed and mattress pads, latex gloves, oxygen masks, catheter equipment, lotions and a file bin with more forms. Every day is scheduled to the max.

“Sometimes, I hear my coworkers talk about having a team lunch in the office,” he says with a smile. “For me, some days it’s an apple at the red light.”

Few Days are Predictable

On this particular day, Tom’s patients represent the spectrum of hospice diagnoses and services.

- A new patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) needs a hospice aide several days a week, prescription renewals and oxygen deliveries.

- A 77-year-old woman who threw a family party just two days ago is now hours from dying, according to calls from her Intensive Comfort Care nurse. Tom alters his morning schedule to visit her apartment, call the doctor, talk with the chaplain (who’s also visiting), consult with the VITAS ICC nurse about a revised care plan and—most importantly—reassure the family that their mother is not suffering.

- A third patient with advanced pancreatic cancer has taken a turn for the worse since last week, and Tom arranges for round-the-clock continuous care services for the next several days so that someone is with her throughout her dying process.

- On the next stop, he spends most of his time talking to a husband whose wife’s dementia makes her withdrawn, moody and occasionally out of touch with reality. Her vital signs are good, so Tom makes sure she has necessary medicines and that her husband has the emotional support he needs in his role as primary caregiver.

- By late afternoon, his last patient, also diagnosed with COPD, gets a routine check and a bandage change for a broken arm that is healing after a fall several months ago.

The Biggest Challenges: Acceptance vs. Denial

Tom understands that his educational and listening skills are as valuable as his clinical skills. He spends time on many visits explaining what hospice provides: comfort care, psychosocial support, and pain and symptom management when a cure is no longer an option. The most challenging hospice situations, he says, pivot on the topics of acceptance and denial.

“If the family is in acceptance, they’ll acknowledge the situation by saying things like, ‘I know my mother is going to die. I just want her at home and comfortable.’ That can be very rewarding,” Tom explains. “In those situations, I begin to feel like part of the family, and even after a patient passes, the family will call me in tears and say things like, ‘Thank you, you were so kind to my mother,’ or ‘You have no idea how much you helped us through a difficult time.’ Those are the best days.”

The hardest days involve patients and families who are in denial. Some refuse to accept the finality of a terminal diagnosis. Others might have unrealistic expectations or misconceptions about what hospice care provides. Patients and families also struggle with conflicting opinions and values about end-of-life care.

“I’ve had some really hard times convincing families to make the decisions they need to make,” Tom says. “I have the support of the doctor, the chaplain, the social worker, the bereavement specialist, but because the nurse is the point person for that patient, the decision often boomerangs back to me. I really have to sit down and explain to them what to expect, what they’ll experience, what they’ll encounter and how to focus on comfort care, pain control, dignity, compassion and quality of life in the time that’s left, however long that may be.”

“The Room at the End of the Hall…”

As hard as those situations can be, they’re also the reason Tom chose hospice nursing. It’s part of what he calls the room-at-the-end-of-the-hall phenomenon. Before joining VITAS, the nursing homes and community hospitals where he worked had one or two designated rooms for hospice patients.

“The rooms at the end of the hall were always the hospice rooms,” he explains. “As a staff nurse, we’d run in, give the patients their meds and run back out. But I’d see the VITAS nurses come in and spend time with their patients. They’d really get to know them and talk to their families, understand the family dynamics and stay with their patients until the end. That caught my attention. I remember saying to myself, “Gee, that would be a luxury, to spend quality time with my patients.’ ‘’

Now he’s doing just that. Call him a nursing trailblazer, of sorts, pursuing the profession he loves and providing care at the most important time of his patients’ lives.

Choose a Career with VITAS

We offer a variety of full-time, part-time and per-diem employment opportunities. Employees earn competitive salaries and have the flexibility to choose a benefits package suitable to their own needs and lifestyle.

See Current Opportunities